“We want to be modern” is an exhibition of outstanding Polish design from the 1950s and 60s. Snobs will want to pay it a visit to confirm their taste and expertise, seniors will have an opportunity for nostalgic reminiscence, and average citizens will get a chance to become acquainted with the heritage of Polish design.

“We want to be modern. Polish Design 1955–1968 from the Collection of the National Museum in Warsaw”, National Museum in Warsaw, February 4 – April 17, 2011. Curated by: Anna Maga, Anna Frąckiewicz, Anna Demska

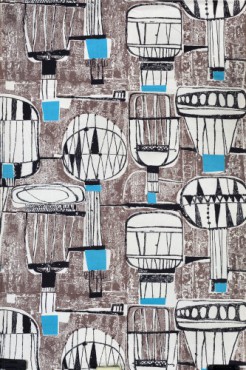

Anna Orzechowska, clothing fabric printed

Anna Orzechowska, clothing fabric printed

on silk, 1956Any museum director or minister of culture would be proud of statistics like these: four thousands visitors saw “We want to be modern. Polish Design 1955–1968” in the first few days after opening. Museum-goers braved long lines to the ticket booth and coat check over the weekend. The skeptics sarcastically chalked it up to effective promotion. Is it even appropriate to measure the success of an artistic venture with raw data?

Enthusiasts of mass education and the expansion of national cultural institutions have reason to be excited: things are finally starting to move. The National Museum in Warsaw has at long last joined the list of venues worth visiting. As it was announced in the mass media, “IKEA just doesn’t cut it anymore.” Now every middle school student will know that before there was IKEA, there were beautiful and practical objects created by Polish designers and Polish factories.

Alicja Wyszogrodzka, decorative fabric

Alicja Wyszogrodzka, decorative fabric

or skirt voucher, 1958News of the National Museum’s previously unseen Polish design collection appeared in the international press over two years ago. The Modern Design Center, tasked with storing and augmenting the collection, was founded in 1979 by Wanda Telakowska, who joined the Museum after being forced to step down as director of the Institute of Industrial Design in 1968.

The regularly expanded collection in Otwock Wielki was only shown to researchers and journalists, as well as to foreign guests of major Polish cultural institutions who were visiting the country on study programs. They remained a “hidden treasure” to local design enthusiasts. What little information there was on the size of the collection (around 24 thousand items), its breadth (ceramics, furniture, fabrics, clothing, glass, and electronics), and the names of its designers, made it all the more tantalizing. Activists, curators, and journalists were up in arms over how the artifacts of our national heritage were being squandered, artifacts that would quicken the pulse of many a design connoisseur in Western Europe and America. “Let Polish design out of the storerooms!” demanded “Gazeta Wyborcza” in March 2010.

Wiesław Sawczuk, decanter and glasses

Wiesław Sawczuk, decanter and glasses

from violet, transparent and smoked glass,

1960“We want to be modern” marks the first public show of the Center’s collection. The exhibition was launched to great fanfare, with a concert, wine, and applause — well deserved, given the importance of the moment. The hitherto warehoused objects deserve to be seen by the masses. Further exhibitions are in the works, as are discussions on creating a permanent space for the collection. For the first show of the series, curators Anna Demska, Anna Maga, and Anna Frąckiewicz selected samples of design from the period between 1955 and 1968, when Soc-Realist propaganda had begun to wane and the socio-political climate grew more conducive to artistic experimentation. Investments in architecture and industrial design contributed to the development of what is now known as “lifestyle”. The exhibition is about more than what beautiful objects people had, it’s about how people wanted to live. The fact that these items were so enticing and remain attractive to this day (owning such an object is cause for pride and social prestige) is the result of conscious efforts on the part of the ruling elite of the time, who wished to bury the past and look forward, creating a new, modern lifestyle. For this reason, the curators have chosen to include film clips from the period which document these aspiration. Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers, Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski’s Their Everyday Life, Leon Jeannot’s A Man with an Apartment, and Jan Batory’s A Cure for Love are screened in their entirety as a part of the educational program accompanying the exhibition.

Teresa Kruszewska, plywood chair, 1956Several themes converge in the main hall. On the walls hang reproductions of posters from the period, exhibition catalogs, and pages from Projekt magazine, which showcased the work of the most talented modern illustrators, designers, and architects: Wojciech Zamecznik, Jerzy Hryniewiecki, Piotr Nagabczyński, and Zofia and Oskar Hansen. Two avant-garde café interiors — Warsaw’s “Błękitna” and Lublin’s “Czarcia Łapa” — announce the arrival of a new aesthetic and show us just how much contemporary urban cafés borrow from the atmosphere of the period. Ignoring the de rigueur stylistic rules of the turn of the 50s and 60s, however, makes modern-day coffee shops appear eclectic by comparison. The characteristic homogeneity of the modern style was not without reason.

Teresa Kruszewska, plywood chair, 1956Several themes converge in the main hall. On the walls hang reproductions of posters from the period, exhibition catalogs, and pages from Projekt magazine, which showcased the work of the most talented modern illustrators, designers, and architects: Wojciech Zamecznik, Jerzy Hryniewiecki, Piotr Nagabczyński, and Zofia and Oskar Hansen. Two avant-garde café interiors — Warsaw’s “Błękitna” and Lublin’s “Czarcia Łapa” — announce the arrival of a new aesthetic and show us just how much contemporary urban cafés borrow from the atmosphere of the period. Ignoring the de rigueur stylistic rules of the turn of the 50s and 60s, however, makes modern-day coffee shops appear eclectic by comparison. The characteristic homogeneity of the modern style was not without reason.

Krzysztof Meisner, Olgierd Rutkowski,

Krzysztof Meisner, Olgierd Rutkowski,

photo camera Alfa, 1959The actual design treasures — furniture, tableware, ceramics, and glass — are displayed in showcases set up on a long stand. According to some, this provides visitors with a quick review of the style of the decade, and enables them to form their own associations between particular exhibits. Others complain that too many objects have been amassed in too small a space, and would prefer to see them placed in some sort of context, a well thought-out composition with other, associated household objects. Only two such reconstructions may be found at the show, both at the entrance. One of them is a residential room designed by Marian Sigmund, with additional ceramics and fabrics.

The chairs, figurines, tableware, glass, and household appliances are all linked by a common style described as “organic”. These simple, elegant forms devoid of straight lines, edges, and corners are inspired by microscopic imagery and abstract painting. The furniture designers borrowed from the art of sculpture, creating sofas, chairs, and tables that can be viewed at all angles. The shape, however, is never disassociated from its function. The rush to achieve progress was based on a belief in the rationality of nature’s own solutions. Telephones, radios, and hair dryers were given an attractive appearance that followed their function.

Danuta Paprowicz-Michno, decorative

Danuta Paprowicz-Michno, decorative

fabric, 1964The colourful decorative fabrics by Aleksandra Michalak-Lewińska, Alicja Wyszygrodzka, Danuta Paprowicz-Michno, and Danuta Teler-Gęsicka are an undoubted hit of the exhibition, and contribute to its energetic and youthful atmosphere. The optimistic patterns, abstract designs, spindle-like forms, simplified human figures, and naïve animal shapes are a testament to the enthusiasm of their creators and their eagerness to have fun and enjoy life. Although half a century old, these pieces have not grown in the least bit retro.

Is there anything missing? Many viewers commented that they would have liked to find out more about the remarkable designers behind the pieces. How did their careers develop? What happened to them after 1968, a date the curators have chosen as a symbolic end to the era of unbridled experimentation? What were their studios, their creative meetings like? How did they share ideas? Some of this can be learned at a series of talks held on Thursdays. But much more is needed. An exhibition as ambitious as this one should tell the designers’ own stories about how they wanted to be modern.

translated by Arthur Barys