David Lynch’s Blue Velvet famously opens with a shot of a family man watering his lawn. It’s an image that embodies the idea of an idyllic America, where firefighters wave from shiny red fire engines, tulips bloom in front of white picket fences, and the lawn – the litmus test of the American suburban, middle-class patriot – is neatly trimmed. The sudden heart attack suffered by the elderly man watering his plants with a garden hose does nothing to disturb that image. But as the camera pans down, digging through the grass, it exposes the full richness of life under the surface, the filth teeming in the soil. This film brings that dark side of life to the surface, only to see it fail.

It Looks Pretty from a Distance, the latest film by Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal, made me feel like I was buried under that lawn. The Sasnals focus on the world’s seedy underbelly. This place is dirty, it’s infested, and it smells like urine. There’s no room for niceties. The views “from a distance” quickly give way to close ups. And it’s not all that pretty from up close.

Paweł

It Looks Pretty from a Distance,

It Looks Pretty from a Distance,

dir. Anna and Wilhelm Sasnal,

Poland 2011, in cinamas since February 2012A middle-of-nowhere village somewhere in Poland. Paweł and a friend of his buy up old cars to scrap for metal in his yard. Paweł lives with his mentally ill mother in a tiny house that appears to be on the verge of collapsing. But seen from a distance, as it is portrayed on the film’s posters, it’s even picturesque, in its own way. Two windows, bare plasterwork, and salvaged roof shingles. Inside, there’s flytape and a mentally handicapped mother who pees wherever she likes, and will run away when left alone even for one minute. When Paweł decides to put her in a home (“She’s not coming back unless it’s in a coffin.”), his girlfriend moves in and promptly sets about cleaning the place up. Out goes the piss-stained bed. Bugs scatter from a wardrobe she takes out into the fresh air. He’s not much of a Romeo, nor is she Julia.

After enjoying a lazy Sunday afternoon by the river, with beer and an equally taciturn friend (remember the sabbath and keep it holy), Paweł disappears into the forest. His girlfriend waits for him in vain. Her father wastes no time in “taking care” of Paweł’s rabbits (“I’ll give ’em back when he comes home”). Paweł’s dog is killed in spite, while his neighbours loot his modest belongings in clandestine midnight raids. In a final spectacle of destruction, the entire village gathers to watch his house go up in flames, after which the entire community falls back into its rut.

But Paweł eventually comes home, and only his death can prevent the imminent conflict.

The man with a film camera

Wilhelm Sasnal’s path to the cinema differs from the careers of traditional filmmakers, who normally study directing in film schools. Sasnal, meanwhile, made it as painter and was famously involved in the debate on Polish history. But as a medium of limited range, painting wasn’t enough for Sasnal.

Swineherd, dir. Wilhelm Sasnal, Poland 2008The artist’s interest in the moving picture started out like that of an amateur armed in an 8 or 16 mm camera. The main character in his 2001 autobiographical comic book Everyday Life in Poland between 1999 and 2001 is never seen without his camera, with which he films the everyday life referenced in the title. Sasnal’s exhibitions have featured his short films and travel journals accompanied by songs, like unconventional music videos.

Swineherd, dir. Wilhelm Sasnal, Poland 2008The artist’s interest in the moving picture started out like that of an amateur armed in an 8 or 16 mm camera. The main character in his 2001 autobiographical comic book Everyday Life in Poland between 1999 and 2001 is never seen without his camera, with which he films the everyday life referenced in the title. Sasnal’s exhibitions have featured his short films and travel journals accompanied by songs, like unconventional music videos.

His forays into the world of feature film began with Swineherd (2008) and The Fall (2010), both with Sasnal as the sole director. It was a jump into the deep end, and was something completely new in Polish cinema.

Uklański, Polański, Sasnal

In the 70s, the group of Łódź Film School students and graduates that formed the Workshop of the Film Form rebelled against the overwhelming role of literature in movies by analysing the medium of film from all possible angles. In one performance staged by Józef Robakowski, for example, the filmmaker used a mirror to reflect the beam of light from the projector onto the audience, who had come expecting to see a film. Today, Robakowski teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts, structural film has earned a place in the history of art rather than in film theatres, and the WFF has taken its rightful place at the Łódź Museum of Art.

As curator Łukasz Ronduda explains, the contemporary relationship between cinema and the visual arts is taking a completely different course. More and more artists have been making feature films. Among the first to do so in Poland was Piotr Uklański, who shot Summer Love (“the first Polish Western”) in 2006. The picture featured a cast of stars: Katarzyna Figura, Bogusław Linda, and Val Kilmer as a cadaver. But what Uklański made was a perfectly professional film about… film. He examined cinematic rhetoric and employed irony by casting a Hollywood star that doesn’t even say a word.

It Looks Pretty from a Distance,

It Looks Pretty from a Distance,

dir. Anna and Wilhelm Sasnal, Poland 2011Wilhelm Sasnal also took an interest in filmmaking at that time. Now Katarzyna Kozyra is making an autobiographical film; she even held an audition for the role of herself last year at Warsaw’s Zachęta Gallery. Norman Leto has become a feature at film festivals. And the Museum of Modern Art, in cooperation with the Polish Film Institute, announced a Film Award for visual artists. The first edition was won by Zbigniew Libera.

Yet all of the above remain niche productions, even outside mainstream film. Their creators can take solace in the famous Woody Allen quote, “I think if people went to the movies, they’d like it. But they just stay home.” With its victory at Wrocław’s New Horizons Festival and its run in cinemas, the Sasnals’ film stands a chance of breaking potential audiences out of that isolation.

The death of the camera

That potential is apparent in Sasnal’s very evolution as a director. Compared to his latest picture, the black and white Swineherd is much more “artsy” and bears traces of the artist’s earlier cinematic experience: it has a certain music video-like quality. Both stories take place in the Polish countryside. In Swineherd such themes as the longing to escape are juxtaposed with hatred directed at strangers who represent that other, better world. The final scene depicts a group of men abusing a film camera. Their aggression towards the Other is transferred onto the camera, which continues to film the events until it itself has been destroyed.

With its formal sensibility and its revelation of that which hides behind the screen, this scene could easily pass for one of the experiments that came out of the Workshop of the Film Form. On the other hand, the film’s final scene depicting the torturing of the camera resembles a technique used by Lars von Trier in The Kingdom, each episode of which he would conclude by appearing in a tuxedo in front of a red curtain and delivering a speech to the viewers, ushering them out of the world of illusion and back into reality, as if to say, “The show is over.”

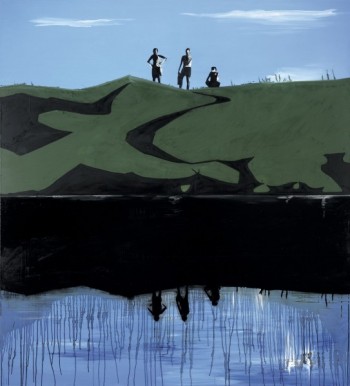

Wilhelm Sasnal, Untitled, 2009, oil on canvas.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Untitled, 2009, oil on canvas.

The painting refers to the location, where

It Looks Pretty from a Distance was made,

photo: courtesy of the artistIt Looks Pretty from a Distance abandons any metanarrative elements. It’s a film about film as much as any painting is about painting. The filmmakers attempt to draw the audience into the illusion of film, rather than keeping them isolated from it. And that’s probably what best proves that Sasnal, an artist thus far associated with the gallery, has crossed over to the other side. The side where films are measured not in minutes, but in feet of celluloid. Yet Sasnal differs from other artists-turned-filmmakers in that he remains a painter. The images, afterimages (!), and long shots reveal the director’s painterly sensibility.

Sasnal, who shares cinematography duties on the film, combines his own intuition for images with Grzegorz Królikiewicz’s idea of the “film space outside the frame”. Some scenes take place behind closed doors: the outside of a car is all we see of the sex scene going on inside. A washing machine drowns out a conversation between the girlfriend and her father as we look on from behind a curtain. Insignificant things are given greater importance. In the same way, the story occasionally stops and gives way to shots of the countryside. It is only there – from a distance – that the view is pretty.

Scream

The village that the Sasnals portray up close lives by its own set of rules. If you don’t follow them, you’ll end up a loser. Or you’ll fall for a wholesaler who “squirts sperm in every village”. The characters rarely speak. They communicate without words: they know their places and the rules of the game. Perhaps that is their most carnal quality. The rules of psychoanalysis don’t apply here. There are no false bottoms or Freudian slips. With so little talking, how can the characters misspeak? In one distressing scene, Paweł’s mentally ill mother stands in the window, piercing the air with rhythmic burst of inarticulate screaming: a kind of signal to the world. Her voice and her open mouth are the entrance to a rabbit hole – and, as it turns out, the only means of escape.

My impression is that Sasnal applies the same categories to the film as Charles Esche attributes to good paintings: “The best paintings negate the existence of guaranteed safe zones for tradition and political correctness, regardless of whether they are bestowed as aristocratic privilege or imposed in a vulgarly socialist fashion.”

Harvest

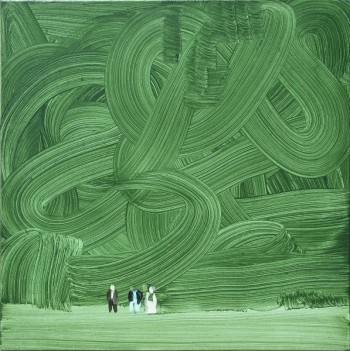

Wilhelm Sasnal, Kacper, 2009, oil on canvas,

Wilhelm Sasnal, Kacper, 2009, oil on canvas,

photo: courtesy of the artistAlthough the Sasnals’ film takes place many years after the war, it does reveal a certain theme present in Polish history, whereby some members of a community suddenly become strangers. The directors even emphasise that it was their intention to create a cinematic response to the debate around the books by Jan Tomasz Gross, which deal with the issue of partial responsibility and the post-war history of Polish Jews. There are no Jewish themes in the film, of course, nor does anyone even utter the word “Jew”. But in one brief exchange, the characters recall an event that occurred during the war, when some local women drowned themselves and their children in the river “out of fear”. “But they weren’t Polish.” Whether or not one discovers the false bottom in the film depends on one’s involvement in the subject. But the Sasnals manage to achieve much more: they engage the audience to the extent that we forget about any cultural topoi. Their vision is convincing. And despite its associations with local Polish debates over Neighbours and Golden Harvest, the topic becomes universal. It becomes a film about neighbours and the harvest.

Anka and Wilhelm Sasnal discuss these themes without resorting to such categories as crime, guilt, or punishment. They assume neither the perspective of the victim nor the perpetrator. No one is reproached, no one is stigmatised as the victim. They achieve this by eschewing the burden of Catholic morality (the church is part of that ruthless world) and setting aside national problems. Paradoxically, this heavy, sticky picture turns out to be surprisingly fresh. By drawing us into this story, it makes it our own.

It’s easy – too easy – to argue that the film is patronising to rural Poland and its inhabitants. If so, what is left?

Can you be happy in the country?

Once again, the countryside is a separate place that has its own set of “natural” laws. Winters are cold, summers are hot, and the earth isn’t necessarily round. “I’ve been across the river and there ain’t nothing curving over there”, says Kaziuk, the main character in the film Konopielka (directed by Witold Leszczyński, based on the book by Edward Redliński). The earth is just there. In It Looks Pretty from a Distance, the boundaries of the world aren’t even marked by the towns of Supraśl or Białystok. The world ends at the edge of the forest, the river, and the railroad tracks.

Wilhelm Sasnal, Shoah (Forest), 2003, oil on canvas,

Wilhelm Sasnal, Shoah (Forest), 2003, oil on canvas,

photo: courtesy of the artistThere’s nothing left of the supposed order that collapses in Redliński’s novel. “I dreamt that they were beating the children. Does that mean we’re having guests?”, says Kaziuk’s wife Hanka (excellently portrayed by Anna Seniuk) as she wakes up. Instead of guests, they get a school and electricity – the danger comes from outside. In Redliński and Leszczyński’s depiction, the village is no longer the pre-World War II countryside idealised in Polish modernism. It’s a gray, backward, superstitious world governed by its own, brutal order. Changes provoke conflict between supporters of the new and the old, as symbolised by the tragically absurd argument over whether rye may be harvested with a scythe (“Is work just about getting it done faster?”) or with just a sickle, in keeping with tradition.

Even if there is a village like the one portrayed in It Looks Pretty from a Distance, it’s more of a metaphor: it’s everywhere and nowhere, and can’t really be placed within the context of any historical or social processes. But it’s certainly a village that never benefited from the changes brought about by progress, including that of recent years. The inhabitants have long ceased to be exotic characters. Now, they are merely trapped. It’s no coincidence that the film opens with a telling scene that shows men setting up animal traps.

Shamelessness

While Swineherd talked about the urge to escape, about dreams of another world, one symbolised by a scrapbook of clippings from glossy magazines, and about the distrust of strangers, It Looks Pretty from a Distance deals with the impossibility of return. There is no cleansing rain. The crime is never followed by punishment. Nor does anyone stop to consider whether the crime was one of passion. Dostoyevskian dilemmas are superfluous.

When, a few years ago, Sasnal’s Zachęta exhibition, “Years of Struggle”, landed him on the front pages of newspapers, the artist took every opportunity to stress how ashamed he was. He was ashamed of those who ruled Poland (the Kaczyński twins, Giertych) and he felt shame for the unacknowledged dark pages of Polish history. It was as if he saw a piece of himself in the picture of the Pole as a pig that he himself painted based on Art Spiegelman’s controversial comic book Maus. But shame equals powerlessness and malaise – precisely what It Looks Pretty from a Distance delivers us from.

translated by Arthur Barys