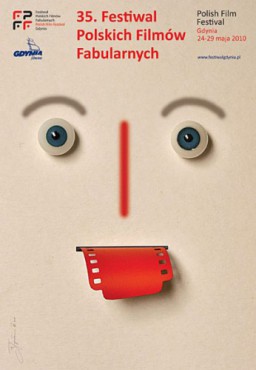

The truth about the Gdynia film festival can be found in its promotional posters. This year’s shows a kind of face or mug, a red (drunkard’s?) nose, eyebrows and eyeballs like from a puppeteer’s prop room, and a stretch of film tape for the tongue. Chaotic and uninspired, plus the tongue. Out of breath when rushing to see the next screening? No, it’s rather a tongue stuck out by the filmmakers at the audience. One might hope to either nod their head in approval or at least yell out “Scandal!” after the Golden Lion award ceremony. Nothing of the sort. The lukewarm Gdynia film festival was nothing more than a praise of mediocrity.

35th Polish Film Festival in Gdynia,

35th Polish Film Festival in Gdynia,

24-29 May 2010

Female Doings and Male Deeds

The main award went to Jan Kidawa-Błoński’s Różyczka (Rosie), a movie about a primitive political cop, a sophisticated writer, and a woman who, working for the former, denounces the latter. A movie done the straight and narrow way, trying to show that, in all fairness, “nothing was as it seemed.” So bent on explaining that everyone had their reasons (the cop loves the girl but has his job to look after; the girl loves the writer but has no choice but to rat him out; the good writer loves the girl, but also the Latin language, French wine, and Miłosz) that it exempts the author from the need to take any stand. The acting award for Magdalena Boczarska, who alone saved several subplots in Różyczka, was bulls-eye. During the literary meeting scene, she and Andrzej Seweryn start an acting duel that quickly turns into a contest of two aesthetics. He mentions Mickiewicz and, virtually standing at attention, twitters about artist values while she takes down his words on a typewriter and signals with delicate glances that his impressive persona arouses not lofty patriotic feelings in her but simple lust. Chrzest (Christening), dir. Marcin WronaThe Silver Lions went to Marcin Wrona for Chrzest (Christening), another story, after the debut Moja krew (My blood), about why it’s a man’s life that’s tough and why the male cause is the only right cause. Wojciech Zieliński and Tomasz Schuchardt, jointly awarded for their roles, play old friends. One wants to baptize his child but is running out of time (because there’s a mob contract out on him). The other has just completed his military service and is to be the godfather. The girl, meanwhile, has been robbed of her own language, her own emotions, and although the two protagonists try to convince the viewers that it’s all about hetero love, in reality it’s only them being pals that matters. A storyline motif from Wrona’s previous film is repeated here: the men decide what will be best for the woman, who are treated as a mere gadget, while she’s tending the barbecue. Plus some Polish-style gangster stuff: urban slums, white T-shirts, worn leather jackets, brutes in expensive suits going philosophical, and cheap whores. In the foreground: male stuff and the archetypal Polish Mother, taken from behind by the sink or on the bathroom floor in front of a crying baby.

Chrzest (Christening), dir. Marcin WronaThe Silver Lions went to Marcin Wrona for Chrzest (Christening), another story, after the debut Moja krew (My blood), about why it’s a man’s life that’s tough and why the male cause is the only right cause. Wojciech Zieliński and Tomasz Schuchardt, jointly awarded for their roles, play old friends. One wants to baptize his child but is running out of time (because there’s a mob contract out on him). The other has just completed his military service and is to be the godfather. The girl, meanwhile, has been robbed of her own language, her own emotions, and although the two protagonists try to convince the viewers that it’s all about hetero love, in reality it’s only them being pals that matters. A storyline motif from Wrona’s previous film is repeated here: the men decide what will be best for the woman, who are treated as a mere gadget, while she’s tending the barbecue. Plus some Polish-style gangster stuff: urban slums, white T-shirts, worn leather jackets, brutes in expensive suits going philosophical, and cheap whores. In the foreground: male stuff and the archetypal Polish Mother, taken from behind by the sink or on the bathroom floor in front of a crying baby.

Uneven Debuts Erratum, dir. Marek LechkiMarek Lechki’s Erratum welcomes us with the sight of crashing waves that resemble blue flames (symbolizing the initial coolness and final ardor of the main character’s feelings). Then we meet Michał, a guy who left for Warsaw in his young days and let himself get trapped in the cage of a corporate job. Of course he played in a rock band before. Of course he wanted to study music but ended up studying accounting. Of course fate will send him back to his home town where his abandoned father and an equally abandoned band-mate are waiting. Will coming to terms with the past bring an acceptance of the future? Lechki, winner of the debut and the press awards, ends the film abruptly and leaves the question unanswered. Ultimately, this saves the straightforward, though formally sophisticated and ascetic, story. And although the other debutants (e.g. Sławomir Pstrong with Cisza [Silence] or Tadeusz Paradowicz with Fenomen [Phenomenon]) showed films that could serve as basis for a theory about the devaluation of the main competition, the jury ignored Paweł Sala’s fantastic Matka Teresa of kotów (Mother Teresa of the cats) when awarding the debut prize.

Erratum, dir. Marek LechkiMarek Lechki’s Erratum welcomes us with the sight of crashing waves that resemble blue flames (symbolizing the initial coolness and final ardor of the main character’s feelings). Then we meet Michał, a guy who left for Warsaw in his young days and let himself get trapped in the cage of a corporate job. Of course he played in a rock band before. Of course he wanted to study music but ended up studying accounting. Of course fate will send him back to his home town where his abandoned father and an equally abandoned band-mate are waiting. Will coming to terms with the past bring an acceptance of the future? Lechki, winner of the debut and the press awards, ends the film abruptly and leaves the question unanswered. Ultimately, this saves the straightforward, though formally sophisticated and ascetic, story. And although the other debutants (e.g. Sławomir Pstrong with Cisza [Silence] or Tadeusz Paradowicz with Fenomen [Phenomenon]) showed films that could serve as basis for a theory about the devaluation of the main competition, the jury ignored Paweł Sala’s fantastic Matka Teresa of kotów (Mother Teresa of the cats) when awarding the debut prize.

Although Sala’s film was inspired by a crime blotter, it is far from tabloid generalisations. Telling the story of a crime committed by two brothers in non-chronological order, he opened the way for stylish psychological narration. The ellipsis becomes the key means of expression in this drama. Restricting the story to crucial moments during the final thirteen months before the killing, the director dilutes facts and divides responsibility between many factors, engaging the viewer in a demanding game, at stake in which is one of the many fragments of the truth (it’s another matter that the protagonists spend too much time in electronic game parlours and stare too tellingly into the pixels, which suggests that the “new-media” reality has turned them into monsters).

No Risks Taken

Equally interesting films were few and far between. The safe and tested reigned supreme. Dorota Kędzierzawska played on the run-of-the-mill theme of sad and dirty children (Jutro będzie lepiej [Tomorrow it’ll be better]), Ryszard Brylski came to Gdynia with an epigone of magical realism (Cudowne lato [A wonderful summer]), and Feliks Falk proposed a predictable and lengthy novella from WWII-era Warsaw, awarded, for no apparent reason, for screenplay and direction. The best entry in this company came from Jan Jakub Kolski, whose collaboration with writer Włodzimierz Odojewski had produced a satisfactory result. And although Wenecja (Venice) remains an uneven work, it performs nicely as a low-key drama about the power of the childish imagination, freed by boredom, anger and frustration. Święty interes (Holy business),

Święty interes (Holy business),

dir. Maciej WojtyszkoOne thing is obvious: the films shown in Gdynia this year were incomplete. They gave the impression of having been released too early, written and directed hastily. Interesting concepts weren’t developed, the authors stopped halfway – the scathing and uncompromising soon became polite, shy and timid. In his quite funny Święty interes (Holy business), Maciej Wojtyszko had a chance to intelligently mock the Polish religiousness and the God-Honor-Homeland rhetoric. His two protagonists – wheeler-dealer brothers – are played by Adam “Father Popiełuszko” Woronowicz and Piotr “A Man Who Became Pope” Adamczyk. Their object of desire, and the story’s trigger, is an old Warszawa car believed to have once belonged to Karol Wojtyła, the later John Paul II. The movie verges on the banal time and again and although it never actually crosses the line, it still leaves the viewer unsatisfied – the sting of this satire proves particularly blunt. Skrzydlate świnie (Winged pigs),

Skrzydlate świnie (Winged pigs),

dir. Anna KazejakIn Skrzydlate świnie (Winged pigs), Anna Kazejak infiltrates the world of third-division football fans. The camera pushes its way through the crowd, stopping at the sweaty, red faces, recording every grimace of anger and satisfaction, surrendering to the dynamism of the action taking place at the stadium (though not in the actual field). The director embroils her protagonist, the diehard Oskar, in several interesting dilemmas. There’s a newborn baby at home, the football club gets sold, his buddies drag him down, put shortly – it’s time to finally start living. But how? The solution, in family-cinema style, is the author’s deft sidestep. In her poster-like world, an “inner transformation” is as easy as gestures of forgiveness, sacrifice or love.

The reverse of these innocent and basically successful movies that had fallen victim to a strategy of half-measures is Trzy minuty. 21.37 (Three minutes. 21.37). The director, Maciej Ślesicki, went all the way. The first scene where we watch Earth from outer space to off-screen narration about a spiritual energy enchanted in the Polish people (and released by the Pope’s death) is already the ultimate in bad taste. Then, although this may be hard to believe, it gets even worse. You’ll find virtually everything here: a burnt-out filmmaker and a boy who can’t afford to buy a pair of shoes; a lone avenger in a trench coat and Bogusław Linda doing the Great Improvisation (“You’ve tried me, God, tried me hard. Like you did our Pope”); The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and Maria Konopnicka’s Our Jade. And, for dessert, a scene from the viewpoint of a drunken horse. To use a metaphor suggested by a friend of mine: Ślesicki threw many balls in the air and caught none.

*

What else? Polish children still play unevenly (for the one boy in Wenecja there was one robot-girl in Joanna). In the ranking of musical instruments, the trombone, accordion, and anemic piano still reign supreme. Crude off-screen narration remains popular. Each screening was preceded by a Polish Film Institute commercial made by Paweł Borowski (Zero). A hefty budget, big names, a paean to the Institute that fights for a better tomorrow for all filmmakers. Ironically, the festival’s most interesting event had nothing to do with either the PISF or Polish cinema in general. Far from all the glitz, the sequins and the camera flashes, in a special screening, a Polish woman filmmaker from Hollywood, Agnieszka Wojtowicz-Vosloo, got her ninety minutes. Her thriller, After Life, had both a concept and its perfect execution; introduction, development, conclusion; awareness of content, sense of form.

And for the very end, a genre scene. A hallway of the Silver Screen cinema. At the entrance to the screening room, an elderly gentleman, in a peaked cap, stooped, his eyes fixed on the doorknob. “Entering?” I ask him, cause I’m slightly late myself, anxious and not sure which way to pass him from. “Well, I’m a bit afraid, you know?” he says. Unfortunately, I do.

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak