In her book Portret wielokrotny dzieła Aliny Szapocznikow (A multiple portrait of Alina Szapocznikow’s work), Agata Jakubowska interestingly comments on the reception of the artist’s oeuvre. She compares the attitude of her interpreters to Sigmund Freud’s attitude towards his female hysteria patients, as described by Lucy Irigaray. According to the latter, Freud initially listened to his hysterics, but with time grew less and less interested in what they had to say and focused instead on constructing a hysteria theory. Jakubowska points out a certain similarity: “If we switched Freud for Szapocznikow’s interpreters, we could claim with certain exaggeration that she faces the same risk.”

Listening to the Sculptures

Out of My Mouth

The Photosculptures of Alina Szapocznikow Exhibition

3 June 2010 – 29 August 2010 Mezzanine, Leeds Art Gallery

Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, U.K.

We can suggest that the exhibition Awkward Objects that was held at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art in 2009 was organised to avert that risk and that its purpose was to “listen” to what Szapocznikow’s sculptures have to say. The show was curated by Joanna Mytkowska and Agata Jakubowska. The latter’s 2008 book was an important step on the path of investigating the work of the prematurely deceased artist. Other Polish researchers and curators have been involved in the same process for years, to mention but Jola Gola, author of a catalogue raisonné of Szapocznikow’s works, or Anda Rottenberg who in 1998 organised her large exhibition at the Zachęta, to this day regarded as controversial.

In recent years, Szapocznikow has increasingly gained international recognition. Her Photosculptures portfolio was shown in the Documenta in Kassel, and following her exhibition at the Broadway 1602, curated by Anke Kempkes, several of her pieces were purchased by the MoMA.

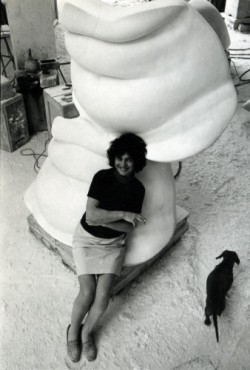

Alina Szapocznikow and her “Grands

Alina Szapocznikow and her “Grands

ventres”, 1968The Warsaw Museum of Modern Art’s involvement is certain to mark a turning point. First of all, a qualitative change is taking place in the critical reflection on Szapocznikow’s oeuvre. The purpose of “listening” to her works is not to discover any single truth about them but to point out a diversity of the possible interpretations and positions. The “view from outside” that Jakubowska mentioned when opening the exhibition accompanying conference has been a very important contribution. Among the participants were leading feminist art historians, such as Griselda Pollock or Sarah Wilson.

Biography, Biographies

Even during a cursory reading of publications devoted to Szapocznikow, one is struck by how much the reception of her work has been related to her biography – camp experiences, health issues, premature death, but also her “cheerful nature”. The issue returned time and again during the conference. Piotr Juszkiewicz talked even about a suspension between “biographobia” and “biographilia”. The artist herself, in a 1969 film by Jean-Marie Drot, presented in the exhibition, says that “All artists are a bit exhibitionistic,” to then add “We always talk too much about our lives.”

The exhibition Awkward Objects avoided overemphasising the self-referential trope in Szapocznikow’s art and interpreting it through the biographic key. This is not, of course, to prove that the artist’s personal experiences had no influence on the shape and subject matter of her works. What is important is for these facts to not narrow down the reception and not erase the potential meanings. The curators succeeded in this. The exhibition was dominated by sculptures: some placed on floor level, others on low plinths, still others, small knick-knack types of objects, in glass cabinets.

Alina Szapocznikow. Documents. Works. Interpretations. Connie Butler.

from Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw on Vimeo.

Media Presence

The curators’ approach was revealed in the very title of the show, which shifted emphasis from the person of the artist to the objects produced by her (the title derived from a quotation from the artist: “I just make awkward objects”). It is surprising that the process of “disenchanting” Szapocznikow’s work gains momentum by being placed in the context of pieces by other women artists: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, or Maria Bartuszova. The curators have avoided the dead-end of demonstrating a common female idiom, which has often narrowed down the message of women artist exhibitions. A different process took place here: in the fine company, Szapocznikow’s sculptures revealed potentials of multilevel interpretations.

photo Jan SmagaBut the curators went even farther than that: they were interested in the process of the creation of media presence and myth. They ask what happens when personal memory turns into an art-history legend. They point out common traits in the images of Eva Hesse, Pauline Boty, and Szapocznikow herself (the practice of posing for photographs among sculptures in the studio, using similar worn metaphors and comparisons) in order to demythologize those images. Thus, using classic curatorial measures, they also criticise the language in which the artists’ work has been interpreted. This critical function was performed in the show by works by Pauline Boty and Paulina Ołowska.

photo Jan SmagaBut the curators went even farther than that: they were interested in the process of the creation of media presence and myth. They ask what happens when personal memory turns into an art-history legend. They point out common traits in the images of Eva Hesse, Pauline Boty, and Szapocznikow herself (the practice of posing for photographs among sculptures in the studio, using similar worn metaphors and comparisons) in order to demythologize those images. Thus, using classic curatorial measures, they also criticise the language in which the artists’ work has been interpreted. This critical function was performed in the show by works by Pauline Boty and Paulina Ołowska.

Sculpture-Key

Most of the exhibition’s tropes focused in Souvenirs from a Happy Woman’s Wedding Table, originally presented in the artist’s last solo show at the Aurora Gallery in Geneva in 1971. It has been recreated here with the maximum precision possible (the location of some of the works once forming part of it is unknown). In Geneva, the artist had arranged her pieces like leftovers from a meal, scraps, traces, and relics.

There were casts of the artist’s own body, a knick-knack/toy with a mouth cast, a self-portrait from the series Tumours Personified, and finally objects with photographs embedded in plastic. Analysing the “awkward objects” collected on the table, we find erotic and abject forms. Issues of female image and self-portrait, of memory and history, crisscross here.

Two works displayed on the wall, Souvenir I (1971) and Le Monde (1971), peculiarly resembled private, intimate treasures. They were like old, tattered photographs or like a newspaper that someone has kept and we don’t know why.

“She Remembers Too”

Souvenir I has been interpreted as the artist’s return to traumatic memories. Szapocznikow avoided commenting on the time she had spent in ghettos and concentration camps. “She avoided the subject virtually obsessively,” said Aleksander Wojciechowski.

In one scene of the above mentioned film, we saw the artist in her Warsaw studio. It is the late 1960s. Asked about her wartime experiences, Szapocznikow tries to change the subject: “It’s indecent to talk about it.” But earlier the camera notices The Exhumed and the narrator says, “She remembers too.”

Jakubowska writes that Szapocznikow “avoided the subject but that does not mean that her wartime experiences were not reflected in her art.” The subject was present in her monument designs of the mid-1950s (Auschwitz monument, 1958; Warsaw Heroes monument, 1957). When it returned in the 1970s, it was no longer in the context of collective memory but of the personal one.

photo Jan SmagaIn Souvenir I, Szapocznikow has embedded in polyester a blow-up of her own photograph as a child (from the 1930s) and photographs of women, most likely Auschwitz prisoners, of which Jakubowska writes that it “belongs to (…) such that (…) we explicitly recognize as representing victims of a crime.” Using psychoanalytic categories, she likens Souvenir I to an “event”. In her view, the artist stopped at the stage of melancholy because “mourning is possible when a traumatic experience starts to be perceived as something from the past, something that is remembered rather than constantly relived.”

photo Jan SmagaIn Souvenir I, Szapocznikow has embedded in polyester a blow-up of her own photograph as a child (from the 1930s) and photographs of women, most likely Auschwitz prisoners, of which Jakubowska writes that it “belongs to (…) such that (…) we explicitly recognize as representing victims of a crime.” Using psychoanalytic categories, she likens Souvenir I to an “event”. In her view, the artist stopped at the stage of melancholy because “mourning is possible when a traumatic experience starts to be perceived as something from the past, something that is remembered rather than constantly relived.”

Humour

Souvenir I was mentioned during the conference by Griselda Pollock who talked about what happens with the blow-up of a picture from pre-war holidays embedded in the transparent plastic. Pollock argues that the blurry, context-less photograph offers no clue as to the girl’s mood. Inspired by Bracha L. Ettinger’s theories, Pollock is interested as much in the artist’s position as in the process of the work’s reception, especially the way viewers deal with the trauma encoded in it.

During one of the conference’s discussions Pollock suggested that the teasing question of “who really talks to us when we look at a sculpture” is the most urgent one. The curators were aware of this. As a result, the exhibition was a breath of fresh air in the heavy atmosphere that has grown around the artist’s oeuvre. Awkward Objects vividly revealed the unique humour present in Szapocznikow’s sculptures as well as the issue, usually ignored in analyses of her work, of the abject.

Final Years

The show focused on Alina Szapocznikow’s work in the last ten years of her life, dominated by body part casts, plastics, and photography, the latter as a sculpture feature, embedded in polyester. Our attention was drawn to the monumental marble Big Bellies (1968) from the Rijksmuseum in Otterlo, presented in Poland for the first time.

The two magnified forms of the female belly placed one atop the other are both erotic and inaccessibly aloof. As Jakubowska notes, the belly “cannot (…) unlike the legs, breasts or mouth, be turned into a fetish. It eludes its logic.” In a smaller scale, the marble abdomens could become a knick-knack, a gadget. Enlarged to monumental scale, they stress the element of humour and the absurd. Also, the pottery shown in the exhibition is caricatural – terra cotta half-faces, grotesquely twisted, flowers growing out of them. Humour dominates in the Illuminated Mouths, lamps made by Szapocznikow from 1966, with lip casts for lampshades.

Nor can we ignore the mocking tone of the Desserts, in which ice cream delicacies have been replaced by female breasts in icing-pink hues. As a body part, breasts also “serve” feeding. Szapocznikow’s art perversely combines erotics with cannibalism. Her other erotic objects seem like exercises in rebellious design that uses the human body as the matrix. The artist planned to start mass-producing Bellies casts as pillows. The lip lamps or pottery pieces could also serve as prototypes for mass production.

Fashion Show

A different approach to the body was present in the extremely interesting confrontation of the works of Szapocznikow and Louise Bourgeois. What dominates is Bourgeois’s Avenza Revisisted II (1968-1969) from a series that – according to the artist herself – captures the “anthropomorphic landscape”. “Our own body can be considered from the topographic point of view, as a land of hills and valleys, caves and holes,” she said. Then there was Szapocznikow’s Trap Seat (1968), resembling a crater with lava flowing but also a case of the human buttocks, and Under the Dome (1970), a fragment of a strange, deserted, virtually scatological landscape.

photo Jan SmagaWe saw abstract biomorphic forms in drawings by Szapocznikow, sculptures by Bartuszova and Bourgeois. The exhibition was reminiscent of the Fashion Show project at the Hamilton Gallery in New York in 1978. Models paraded in Bourgeois-prepared costumes, covered with projections resembling nipples or udders but also phallic forms, utilising both male and female features.

photo Jan SmagaWe saw abstract biomorphic forms in drawings by Szapocznikow, sculptures by Bartuszova and Bourgeois. The exhibition was reminiscent of the Fashion Show project at the Hamilton Gallery in New York in 1978. Models paraded in Bourgeois-prepared costumes, covered with projections resembling nipples or udders but also phallic forms, utilising both male and female features.

Towards Pop Culture

Awkward Objects also presented the less known aspects of Szapocznikow’s work. They highlighted its ties with pop culture and design, as well as conceptual projects (My American Dream, 1971, or Operazione Vesuvio, a skating rink inside the Vesuvius crater, 1972). Among the pieces on display was Goldfinger (1965), a figure made up of a gold-patinated concrete form and a car coil spring in which body and machine become one (a theme also present in drawings by Szapocznikow and by Eva Hesse). Placed atop a chunk of scrap, the huge golden phallic form reveals important pop culture influences.

Whatever path we took throughout the exhibition, we always ended it in front of the Souvenirs from a Happy Woman’s Wedding Table. What were these souvenirs? A blurry image of a forgotten past coexisted with a melting self-portrait, and a kitschy mouth-on-a-stick with repulsive lava that has trapped scraps of stockings and bodily waste. How different this table is from Judy Chicago’s famous The Dinner Party (1974-1979), a triangular table with fully set places for famous women from various historical periods.

It was a resounding feminist statement and a tribute to the predecessors’ achievements, as well as a plea for a feminist genealogy. Szapocznikow’s table features rotting relics and stale mementos, remnants of desire and echoes of traumas.

Indeed, privatization (but not necessarily biographism), something that Anda Rottenberg mentioned during the conference, is an important trait of Szapocznikow’s art. Awkward Objects by no means negated it, at the same time pointing to the multi-aspectuality of the sculptor’s body of work.

translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak